Why Should Witches be Consider as a Feminist Icon?

By Hannah Dwyer

Abstract

This paper will explore why women who were accused of witchcraft should be recognised as feminist icons for women today. Though witches now are often thought of as being old, green skinned women who ride their broomstick on their hunt for innocent children. For years the witch has been the monster to scare people into accordance to the society norm. However, in recent years, the witch has been transformed from the scary old lady to a powerful inspiration to empower women today. This paper will start by exploring what, in reality, is a witch. Was she magic or was she actually a scientist who was stopped by the patriarchy? Also, this paper will investigate why the image of the witch is changed due to one perspective by looking at Circe, the Ancient Greek witch, through Homer’s Odysseus, Madeline Miller’s Circe as well as various artwork. Additionally, this paper will look at 21st century interpretations of witch in Stephen King’s novel Carrie, Amanda Lovelace’s collection of poetry The Witch doesn’t Die in This One and Jeanette Winterson’s novel The Daylight Gate.

Throughout history many women have proved that they are just as powerful as men by standing up against the patriarchy and proved that women should be seen as men’s equal. From Lady Godiva, Queen Elizabeth, Joan of Arc, Harriet Tubman, Hua Mulan and many more. However, witches were the first example of women forming together to rebel against the sexist norms of society. Also, the witch wasn’t born into power through nobility or wealth to aid her in her struggle but yet they still demonstrated that they were an equal match to their male counterparts. Witches have been a part of multiple societies across the globe for thousands of years. From Cire to Morgan le Fay to Marie Laveau, “the witch has long existed in the tales [where] we talk about ladies with strange powers that can harm or heal.”[1] Although people of all genders have been considered to be a witch, it is a word that is now firmly only associated with women. The persona of the witch has definitely changed since the magical creature first came into existence in folk lore and mythical legends. Witches “were people who thanks to their abilities set themselves apart from the rest of the community.”[2] The common idea of the witch is that she is “placed at the boundaries of life and death, directing evil spells against single individuals or whole villages in order to steal or destroy their physical and spiritual existence, witches’ work can be equated with the activities of supernatural beings, particularly those mysterious creatures identified as fairies since antiquity” (Matteoni, 2009).[3] Likewise, the witch has often been “someone to fear, an uncanny Other who threatens our safety or manipulates reality for her own mercurial purposes; She’s a pariah, a persona non grata, a bogeywoman to defeat and discard (Grossman, 2019).”[4] Traditionally, witchcraft was the exercise or invocation of alleged supernatural powers to control people or events, practices typically involving sorcery or magic. Although “defined differently in disparate historical and cultural contexts, witchcraft has often been seen, especially in the West, as the work of crones who meet secretly at night, indulge in cannibalism and orgiastic rites with the Devil, or Satan, and perform black magic” (Lewis, 2021)[5].

However, it seems that “the witch has done another magic trick, by turning from a fright into a figure of inspiration.”[6] Wicca is a “predominantly Western movement whose followers practice witchcraft and nature worship and who see it as a religion based on pre-Christian traditions of northern and western Europe, adherents of Wicca worship the Goddess, honour nature, practice ceremonial magic, invoke the aid of deities, and celebrate Halloween, the summer solstice, and the vernal equinox.” As the 21st century began, “Wiccans and Neo-Pagans were found throughout the English-speaking world and across northern and western Europe,”[7] and it is now estimated that “the number of adherents ranged dramatically, with the number of Wiccans in the United States believed to be between 100,000 and more than 1.5 million.”[8] Pop culture, that is fuelled from popular Tv shows, books and films like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Sabrina the Teenage Witch and most significantly the Harry Potter series, have transformed the witch from a symbol of magical being that should be feared and destroyed to a desired source of power and freedom. Though, this does not mean that the witch is now never looked at in a negative way. There are still images that the witch is an ugly, wicked women who seeks to hurt others within pop culture; for example, the witches in 1993 film Hocus Pocus. Also, the term ‘witch’ is still being used to undermine and insult a women. When “bitch won’t suffice to denigrate a woman, witch adds an element of supernatural evil that has no male equivalent in common use.”[9] Often, “public, powerful, and controversial women from congresswoman Nancy Lewis key to conservative commentator Ann Coulter have been branded with the term- although none more frequently than Hillary Clinton.”[10] “Give her a broom so she can fly away, that witch,” was one of the many times that Trump used the term witch as an insult when talking about during his 2016 presidential campaign. However, this has stop women from perusing the witchcraft and using it as a form of female empowerment as well as in their acts of feminism. There has been a growing development of witchcraft being used, seen and celebrated in everyday media but this has led to a “major point of concern for all initiated witches is the increasing commercialization of what they feel is their tradition,” as now there “is indeed a booming market for witchcraft” (Ramstedt, 2004).[11] What was once feared has now become a part of the capitalist culture. However, this exploitation of witch culture does not take away from the fact that witches were the first group of women displaying feminism and fighting against the patriarchy, making them feminist icons in their own right. This paper will explore the reasons why witches were always feminist icons.

Chapter 1: In Reality, What is a Witch?

Ultimately, medieval and early modern theologians believed that “the devil was the supernatural enemy responsible of the work of witches inside their communities.”[12] The “modern English word witchcraft has three principal connotations: the practice of magic or sorcery worldwide; the beliefs associated with the Western witch hunts of the 14th to the 18th century; and varieties of the modern movement called Wicca, frequently mispronounced ‘wikka.’”[13] During the early modern period, “many people believed that witchcraft, rather than the workings of God's will, offered a more convincing explanation of sudden and unexpected ill-fortune, such as the death of a child, bad harvests, or the death of cattle. When a group of people cannot explain why negative events keep occurring, they need to find an easy way to being false relief to the community; one way to do this was to blame the outcast. Therefore, the witch became the excuse or the scapegoat for anything that seemed to go wrong for that particular community. This is quite possibly why witch-hunting became an obsession in some parts of the country.”[14] In fact, in the UK, 1542 parliament passed the Witchcraft Act which stated that anyone caught performing witchcraft would be punished by death. Even though the act was repealed five years later, it was restored in 1562. In 1604, a further law was passed during King James I reign, who took a huge interest in demonology, and both of the 1562 and 1604 Acts meant the witch trails were transferred from the Church to the ordinary courts. The idea of a witch back then was that she was either an old, withered woman and, overall, formal accusations against witches were in fact poor, elderly women. On the other hand, if the accused wasn’t an old woman, she would then either be wealthy, childless widow, and the men of that community wanted to gain control of her land that was left to her by her husband, or a sexually free woman. Whether the witch is old, young, widowed, wealthy or in control of her sexual desires, she is someone perceived to be out of the patriarchy’s control. Around 513 witches were put on trial between 1560 and 1700 where 122 were executed and the last known execution took place in Devon in1685. Also, the last witch trials in the UK were held in Leicester in 1717. In the end, it is estimated that 500 people are believed to have been executed for witchcraft in England. In 1736, “parliament passed an Act repealing the laws against witchcraft, but imposing fines or imprisonment on people who claimed to be able to use magical powers.”[15] When this Act was introduced in the Commons, “the Bill caused much laughter among MPs. Its promoter was John Conduit whose wife was the niece of Sir Isaac Newton, a father of modern science, although keenly interested in the occult.” To take things even further, “in 1824 Parliament passed the Vagrancy Act under which fortune-telling, astrology and spiritualism became punishable offences.”[16] It is evident that, historically, there was nothing more terrifying for a woman to be accused of witchcraft as legally the odds were stacked against them. In fact, even though “witchcraft was treated as a crime against the state, it was regarded as a greater sin against heaven.”[17] This probably explains that when “under ecclesiastical jurisdiction witchcraft was much more strenuously death with than when it fell under lay tribunals.”[18] Still, we cannot forget that these witch trials were proved to be a “great source of emolument to the church, which grew enormously rich by its confiscation to its own use of all property of the condemned.”[19] This information proves that, at least for some of them, the witch trials were used as a tactic to gain financial abundance by the church from exploiting women in their community.

So, why were older women more likely to be accused of witchcraft? It seems that “old women are presented as corrupted social agents that harm both the individual body and the body politic with their distorted knowledge and evil powers.”[20] Plus, “physical impairments, ugliness and dangerous immorality characterize these figures”[21] that should then be forever known as the evil, wicked women. This is still a concept that is still thriving today, especially in industries like the performance art. Society has the idea that when a woman reaches a certain age, she can no longer serve society. interestingly, this correlation of age and usefulness is connection to a women’s ‘fuckable’ appearance; if a man still wants to have sex with you, then you are still useful. During the early modern period, “life expectancy was shorter owing to frequent epidemics, famines, lack of hygiene and hard physical work and, in general, women were considered to be older earlier than men; they were also valued differently.”[22] Correspondingly, “common notions in natural philosophy characterize the body of post-menopausal females as poisonous, a physical factor to which their allegedly weaker mind and spirit is attributed, supporting an adverse conception of their ontological being.”[23] This belief possibly stems from the idea that women’s are the source of life and when this process of childbirth can no longer take place then this idea of a rotten womb has taken form. We are then left with the connotation that rotten = poisonous. As a result, “aged women, like the disabled, are mostly non-existent in records and traditionally invisible in other fields such as science, philosophy and the arts, and yet they are paradoxically recurrent figures”[24] in literature and art. Even when they do appear in literary texts, they are “generally occupy secondary positions and are unfavourably or comically represented.”[25] In contrast, the “cultural representation of old men, which mostly emphasizes attributes of wisdom and dignity, descriptions of old women centre on their corporeal decay and moral depravity.”[26] Therefore, it appears that women, who could no longer participate in childbearing, were deemed as a useless member of society and were definitely looked down upon, whereas men were seen as wise and able to pass on their wisdom to the next generation. Still, we have to remember that even though these women were written about negatively they were still present enough to be written about. These women were still participating in their sciences like midwifery and herbology despite the risk of being accused and attacked by society. The majority of women who were accused of witchcraft , did so knowingly of the consequences of their actions; they chose to go against the patriarchal norm which subjected women to be treated as property of men. Therefore, witches should be seen as feminist icons because of this fact.

While, “toward the beginning of the IV century, people began to speak of the nocturnal meeting of witches and sorcerers, under the name of ‘Assembly of Diana,” or Herodia” it was not until canon or church law, had become quite engrafted upon the civil law, that the full persecution for witchcraft arose.”[27] Often, “a witch was held to be a women who had deliberately sold herself to the evil one; who delighted in injuring others, and who, for the purpose of enhancing the enormity of her evil acts, choose the sabbath day for the performance of her most impious rites, and to whom all black animals had special relationship; the black cat in many countries being held as her principal familiar to go to the Sabbath signified taking part in witch orgies.”[28] However, regardless of the usual “pretext for witchcraft persecution we have abundant proof that the so-called witch was among the most profoundly scientific persons of the age.”[29] Yet, due to the patriarchy, women were not permitted to continue their studies of natural herbs to make medicines or revising the stars and practicing spiritualism. It is true that “men have, and maintained, power over women in many different ways and at many different levels: at work, in the home, through legislation, and so on.”[30] Furthermore, the church had “forbidden its offices and all external methods of knowledge to woman, was profoundly stirred with indignation at her having through her own wisdom, penetrated into some of the most deeply subtle secrets of nature; and it was a subject of debating during the middle ages if leaning for woman was not an additional capacity for evil, as owning to her, knowledge had first been introduced in the world.”[31] In great belief of their power, women penetrated “into these arcana, women trenched upon that mysterious hidden knowledge of the church which it regarded as among its most potential methods of controlling mankind scholars have invariably attributed magical knowledge and practices to the church, popes and prelates of every degree having been thus accused.”[32] One particular women in society who was constantly penalised for gaining scientific knowledge, that of which went past any mans’ at that point, was the midwife. The midwife was “armed with knowledge of herbology, biology, and, in particular, reproductive health, please predominantly poor, peasant women were easily targets for accusation sorcery.”[33] It was an “era when men knew even less than they do today about women's internal affairs, the midwife held power that stretched past her gender one station;”[34] with insight to the horrors of childbirth, it is no wonder why midwives were a cause of concern for the patriarchy. For centuries, “women were doctors without degrees, barred from books and lectures, learning from each other, and passing on experience from neighbor to neighbor and mother to daughter.”[35] They were called ‘wise woman’ by those who respected them but a witch to the authorities. Now, “witches lived and were burned long before the development of modern medical technology.”[36] It therefore can be argued that witches were just women who has gained more knowledge about the female body compared to her male counterparts. This, therefore, demonstrates that these women were proving that their intellect was possibly greater than the men in her community. In this instance, the witch is a symbol of female thirst for knowledge and is a great example of a feminist act against the patriarchy; consequently, proving that witches were feminist icons.

It is true that “midwives and women who were discovered teaching birth control methods or providing abortifacients or abortions but often also accused of witchcraft.”[37] It was the first noted example of women, widespread around the world, of taking control of their body and seeking out their choice of whether or not they want to become a mother. In 1956 French parliament ordered pregnant women to register their pregnancies and required a witness for their deliveries. Also, while witch hunting continued throughout the midlands, midwifery was forced to become licenced and regulated by the state. It is interesting to see that even to this day, women struggle to have control of their body with abortion laws making it almost impossible for women to make a choice about their own body. It could then be seen that witches were the first women protesting for ‘pro-choice.’ Additionally, the “witch hunts left a lasting effect: an aspect of the female has ever since been associated with the witch, and an aura of contamination has remained – especially around the midwife and other women healers.”[38] We can see this in today’s society when searching for a doctor outfit into google you are given a huge number of websites filled with images of only male doctors. However, if you typed in nurse outfits, you will be met with mainly female nurses’ outfits- even worst you will be met with numerous amounts of ‘sexy nurse’ outfits. This persecution against midwives during the witch hunts has left the assumption that a doctor is a male profession and a nurse (who is classed as below the doctor) is a female profession.

On the other hand, the witch could also be a woman who was in control of her sexuality. Actually, the “most crucial aspect of an explanation of women’s oppression and male dominance is the analysis of sexuality, because it is within the constructs of male and female sexualities that we may observe the central dynamic of male domination over women.”[39] Male and female sexualities are constructed differently from each other where that the “male and female and created through the eroticization of submission and dominance”[40]. In other words, men’s power and women’s social inferiority have been made to be ‘sexy’. The process of constructing women as erotic or sexy objectifies them positioning women as subordinate and men as dominate can be clearly seen within pornography; where it is “acted out within heterosexual relations: where male sexuality objectified by the desired male subject.”[41] Therefore, this has created the notion that “male domination over women may be appear to be natural, but this is not the case.”[42] Women are just as powerful and in tune with their sexuality as men but because this wasn’t the societal norm, it was seen as a threat for male masculinity. Due to the fact that men were supposed to be in dominance of women, it can only be supposed that if a women had power, it could only be perceived has a threat to the male. It has only been in recent year since tv shows like Charmed (1998-2006) and the Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (2018) where the public was presented with a new type of witch: “young, woke, liberated and likely to cast spells that are socially conscious rather than caustic.”[43] Now, the idea has now been presented that a powerful witch, who is secure in her sexuality and power, can work cohesively with men.

Moreover, it has to be noted that although “women, as well as men, did accuse other women of witchcraft,18 and men were also accused of witch- craft, it was men who were the torturers, the jurors, and the judges in these trials.”[44] However, often the witch trials have be “called a “gender-cide” because they were a “gender-selective mass killing,” the difficulty of grouping all witch-hunts, including those of Salem, Massachusetts.”[45]Most historians “recognize that the majority of accused women were believed to have been over fifty years of age and often widows or elderly women who were never married, their most distinguishing feature being that they were without family or male relatives to protect them, although some married women were also targeted.”[46] There is the idea that the “three most distinguishing features of the history of witchcraft were its use for the enrichment of the church; for the advancement of political schemes; and for the gratification of private malice.”[47] As a result, “women of superior intelligence”[48] involved in healing, medicine and anaesthetics for childbirth were accused alongside the “insane, the bed-ridden, the idiotic”[49] as both groups were regarded as threats to the new social order. Furthermore, Silvia Federici’s historical account of the Witch Trials offers an important link between accusations against women and an “increase in the violence against women at specific stages of primitive accumulation;”[50] but also during the emergence of capitalism in early modern Europe, but within colonialism and today amidst globalizations. Also, Federici’s witch combines “the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, [with] the ‘obeha’ woman who poisons the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt.”[51]

Undoubtedly, “over the centuries of witch hunting, the charge of “witchcraft” came to cover a multitude of sins ranging from political subversion and religious heresy to lewdness and blasphemy.”[52] However, there were three main accusations that were repeatedly occurred throughout history. First, witches were accused of every conceivable crime against men- essentially, they were accused of female sexuality. Second, they were accused of having magical powers, specially, healing powers. Lastly, and most interestingly, “they are accused of being organized.”[53] It seems that “not only were the witch’s woman-they were women who seemed to be organized into an enormous secret society.”[54] This is an interesting point as it highlights that witch’s were simply a woman (or group of women) who did not follow society norms proving that they were indeed feminist icons. If we look at a coven as if it was a group of women standing up against the patriarchy and male abuse, then we will see a huge correlation between witch covens and the thousands of women who participated in the #MeToo movement in 2017. Groups of women banded together to stand against the abuse that was perpetuated onto them by men, supported the stories of women who had been abused, raped and harassed.

Ultimately, the pretense of witchcraft is that:

“All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable…Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with the devils…it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men found infected with the heresy of witchcraft…and blessed be the highest who has so far preserved the male sex from so great a crime.”[55]

It all stems from Eve eating the forbidden apple and since then women have always been thought of being weak enough to fall for the devil and his plans. Witches have always been seen as women who have succumbed by the devil. What if the witch was in fact a goddess? The Goddess movement stemmed from the first co witches which practiced "the Craft" as a religion in Los Angeles in 1972. In 1999, Melissa Raphael observed that “contemporary feminist Goddess religion seemed to be making a shift from a mode of predominately non-realism to one that relied more and more heavily on a realist (and monotheistic) perception of the Goddess.”[56]

Today, the Goddess Movement, which evolved from these “early initiatives, has been studied primarily by theologians and psychologists, but has been relatively ignored by sociologists;” but “relatively little is known about the way these groups function, who participates and at what level, and how the worldview of the practitioners is developed and shared.”[57] However, we do know that “all of the women in both groups identified themselves at one time or another as feminist witches, but there were organizational differences between them.”[58] One group called the Dianics, after the Roman Goddess Diana, follow similar worshipping patters to that of “other neopagan groups in the United States and Britain in that they celebrate "sabbats" or holy days based on seasonal cycles, require an apprenticeship and training in ideology and the practice of magic, value female leadership and divinity.”[59] However, the Dianics do differ in that in their “feminist analysis, principal and reject the concept of a male divinity Men are very rarely invited to participate and are not allowed to become members of Dianic covens.”[60] In the end all “feminist witchcraft sees women's oppression and environmental abuse, which they argue are intimately linked, as firmly rooted in patriarchal religions.”[61] This is down to the fact that they claim that “the mythos of God the Father and Creator of everything is a de- vitalized one which fails to address the experience of women's lives, and so can- not possibly link them to the larger social structure.”[62] Specifically, they “focus on the differences between the mythic image of a female divinity who creates life alone in an act of parthenogenesis by reaching within her own body in a physical, material act, and that of a transcendent, celibate male divinity who created life with a thought or a word and who is above and apart from his creation.”[63] We also have to remember why nature is always associated with the mother as well. In the end the “goddess is a metaphor for self-realization, but even more clearly, she is a metaphor for nature.”[64] Hence, this is why witches should be considered as feminist icons and an inspiration for women today.

Chapter 3- Why does the perspective of the Witch matter? Circe the Great Ancient Greek Witch

Throughout history “men have, and maintained, power over women in many different ways and at many different levels: at work, in the home, through legislation, and so on.”[65] Also, men have mainly gained control of the narrative of the witch and it has previously only been taken from the perspective of a man. Frequently, “historical images of witches can be regarded as “woman-hating” or misogynist.”[66]Hence, why the most common idea of a witch has been overly negative and as a result of this the automatic image of a witch is that of wicked woman deprived of any goodness. However, what happens when the witch is descendent from a god? Following the Goddess movement from the previous chapter, one example of a witch that hasn’t seemed to follow the same path of the normal witch in literature and art is that of Circe. Circe is an enchantress in Greek mythology and were known for her vast knowledge of herbs and potions and often pictures with a magical wand or staff and had the ability to turn people into animals. Circe’s legends are best known through Homer’s Odyssey where her she is described as an unforgiving woman who tricks men, entices them to give into desire and turns them into swine. However, recently a new perspective of the witch has emerged through Madeline Miller’s retelling of the myth in her new novel ‘Circe’ (first published in 2018). In this chapter, we will explore how the perspective of the witch can drastically change how the image of the witch is represented.

Originally, the legend of Circe is described as “a ‘dread goddess’ (deine theos, I0.136), the sister of "evil-minded Aeetes," learned in fearful drugs.”[67] It has to be noted that Homer never describes Circe as the old hag we are used to hearing when one describes a witch; in fact, Circe as “beautiful” but “formidable.”[68] Circe is still a descendent of the Gods and therefore does not play by the rules of the mortals. However, because she is described to be a “dread goddess of human voice,”[69] Circe “occupies the ontological niche” where even though she is of divinity, “of another order of being and power than that of mortals and therefore a presence to be feared, she is nevertheless accessible”[70] for mortal men (Yarnall, 1994. Circe isn’t presented as a good character and is still a cautionary tale for men to warn them of women luring them into ungodly behaviours. Through Odysseus narrative, Homer demonstrated that Circe is powerful enough to “bewitch” wolves and lions to make them tame with the use of her “magic drugs.”[71] She led the Odysseus’s men in their “innocence” into her home and fed them well with cheese and wine. The men were allured and trapped “by the sound of her singing,”[72] like as if they were caught in her spell. While the men ate, she introduced a “noxious drug, to make them lose all memory of their native land” and “when they had emptied the bowls which she had handed them, she drove them with blows of a stick into the pigsties.”[73] It is represented in Homer’s depiction that Circe lured Odysseus’s men into her home and happily turned them into pigs for their unfortunate fate of crossed paths with her. It can also be suggested that in Homer’s version of Circe, “Odysseus survived Circe's magic because he was wise and beloved of the muses while his crew succumbed because they were neither;” therefore this suggests that Circe represents a universal idea where “only the good may prevail for they live under a special kind of divine dispensation.”[74] This aligns with the beliefs that were shared by those during the witch trails of Europe. If you a godly, then you will be saved from the evil spells of the witch. Differently, in Madeleine Miller’s portrayal of Circe depicts the witch as a woman, who lives alone, protecting herself from a group of men who could easily overpower her and cause her harm. In Millers story, Circe explains that Odysseus’s men:

“Ate well. They drank more. Their bodies were lumpish here and left with fat, then the muscles beneath were hardest trees. Less cars were long, Brigid and slashing. They had had a good season, then met someone who did not like the thieving. They were plunderers of that I had no doubt for stop their eyes never stop counting up my treasures and they grinned at the tally came to. I did not wait anymore for them to stand and come at me erase my stuff and spoke the word went crying to their pen like all the rest of”[75] (Miller, 2018).

This is a very different take to Homer’s version. Instead of weary men looking for kindness and salvation only to be mercilessly turned in to pigs, the men are seen as the threat. What is also interesting about Miller’s version of Circe’s tale, we as the reader cannot but sympathise for the titled character. If we were a woman alone on an island where a group of, obviously well trained in, war men arrived who perceived to be ready steal from you or possibly worst, wouldn’t you do anything in your power to protect yourself?

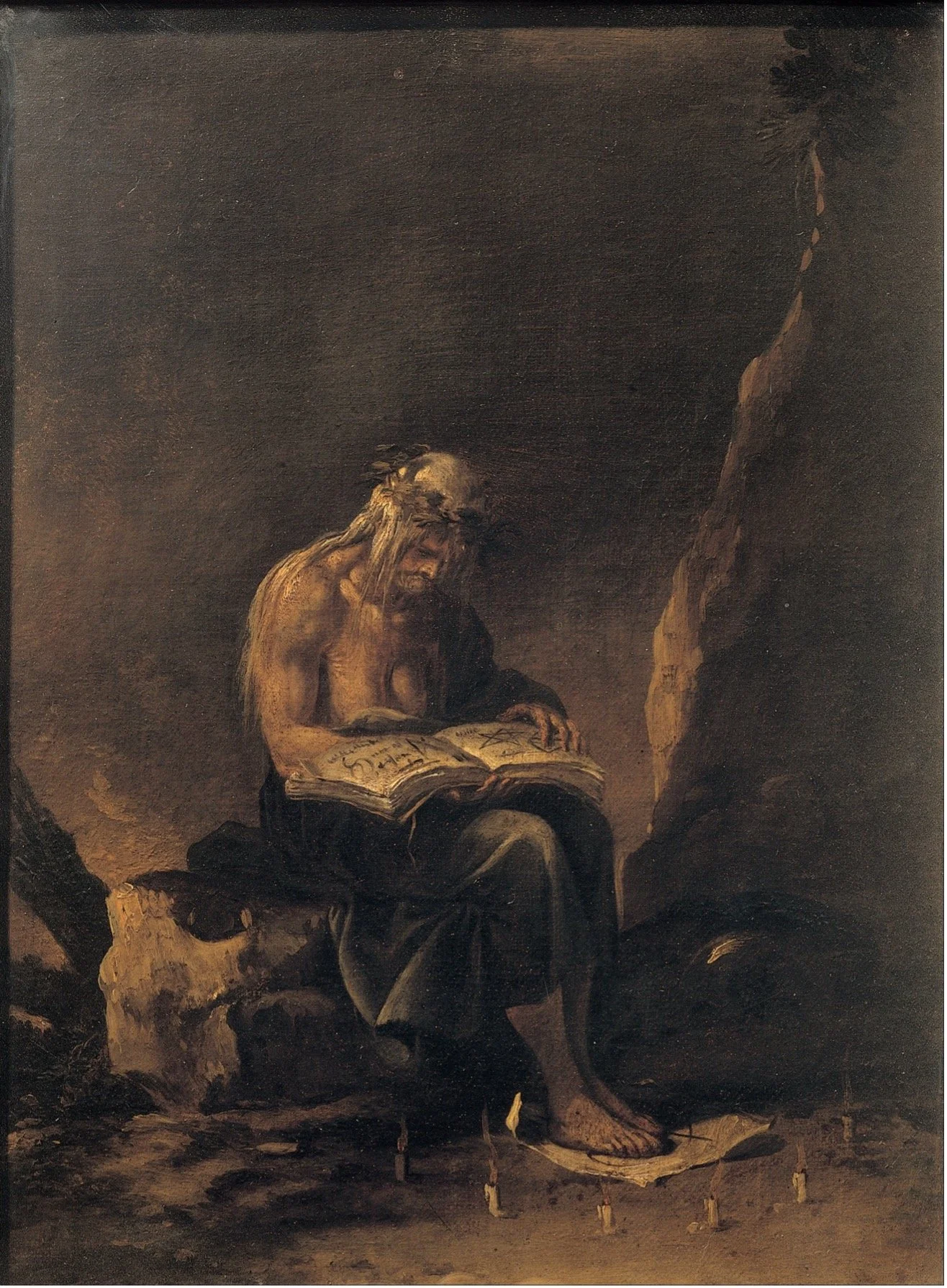

Additionally, “representations of witches in art, primarily by male artists in European art before the twentieth century, and identified elements of misogyny in these depictions of witches.”[76] These “artworks routinely portrayed witches negatively as older women, crones and hags, particularly in fantasies about their sexuality, where they are depicted as voracious or repulsive, and often linked directly to Sabbath rituals as seen in, for example, Francisco Goya’s graphic images of old women and witches in flight and burnt at the stake dating to between 1793 and 1823.”[77] It is theories that these representation of witches are “often discussed as “reflecting” lived realities or as “depictions” of real events, but they are also presentations devised with imagination and fantasy which are not connected to the real.”[78]

However, in artwork, Circe is never presented as an old hag and instead is usually pictured as being a very beautiful woman. John William Waterhouse was inspired by Homer’s Odyssey to paint several masterpieces in his collection of work, one of which being called ‘Circe- Offering the Cup to Ulysses’ (Below). Waterhouse portrays Circe with a “cup in one hand, wand in the other, surrounded by purple flowers, the colour of royalty, offering the potion to Ulysses.”[82] Also, Circe is presented as if she is in fact a queen rather than a magical being as she sits on a golden throne that has two raring lions, which is another node to royalty, with one being on either side of her legs.

Again, in Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione’s etching of Circe, titled ‘Circe with Companions of Ulysses Changed into Animals’, she is again presented as beautiful and surrounded by flowers and plants and holding her wand. Interestingly, in Castiglionr’s etching, Circe also had open books by her feet signifying that she is also well-educated woman.

So, why has literature and art treated Circe fairer then other witches? It is possible that the reason why Circe is portrayed in a kinder fashion was because the artwork was inspired by Homer’s tales, that stemmed from the myth that she was a daughter of a God, and therefore she was more goddess like then witch. It can be suggested that it possible to conclude that “no matter who she is, or whom she supposedly represents, the ‘witch’ remains a benevolent ‘wise-woman’, a victim of phallogocentric hegemonies.”[85] So, though she made be depictured as an old, ugly woman we have to remember that she was just a wise old women and was feared for lack of dependency of men in society. This lack of dependency that the witch possessed is why the witch can be seen as a feminist icon for women today.

Chapter 4- The Modern Witch- How is the Witch Presented in Modern Society?

If you are on Tik Tok, depending on what side of Tik Tok you are on, then you’re for you page could be filled with users posting tarot reading, tips for crystals healing and even spell for love or to break a connection with a toxic person. Witches, spirit channelers or clairvoyants have entered the mainstream media. They are not seen as people that should be feared anymore but a place to guidance. As activism for equality for, race, gender, sexual orientation, religion and class are becoming more and more frequent; more and more “millennial feminists are engaging in ritual, trying out tarot, studying herbalism and following the primordial cycles of the waxing and waning moon.”[86] What once would have “spelled death for women on now life affirming;” however there is still the presence of “misogyny, misinformation, and myth pervade the legacy of the witch.”[87] Still, it seems that the women are now not shying away from their magical practiced anymore and taking control of their inner power. This chapter will explore the modern-day witch and how she inspires feminism from celebrating your period, to exploring your sexuality and, most importantly, fighting for equality within society.

Witches and Rebellious Poetry with Amanda Lovelace’s ‘The Witch Doesn’t Die In This One’

Witches have been oppressed by the male dominate society for many years but from the 21st century onwards have we seen the image of the witch actually fighting back. However, now the “season of the witch is upon us”[88]. In fact, there is a belief of some people that we are magical at heart and that “anyone can be a witch.”[89]Some “people are born into mystical families while others have natural abilities” and others “join covens and houses to be intimated into a certain branch of Magic.”[90]This has been witnessed in tv shows and film but also in literature as well. A unique take of the witch fighting back against their oppressors can be seen in Amanda Lovelace collection of feminist poetry titled ‘The Witch Doesn’t Die In This One’. American poet Amanda Lovelace uses her “poetry as a way of rebellion,” by “writing about feminism, love and selflove, she attempts to empower her reader.”[91] This particular collection of Lovelace’s work focuses on witches and those women speaking out against the cruelty that was perpetuated on to them. What is most intriguing about this about Lovelace’s work is that it can easily be transferred to the modern-day women. For example:

“The boys who spend all their days finger-fiddling

With matchsticks line us up & proceed to stick

Tiny yellow & black truth-telling flowers between

Our teeth. One by one, they ask us if we know

What crime we’re guilty of. After a brief pause to

Gather our thoughts, we say “the only thing we’re

guilty of is being women.” This is simultaneously

the right & wrong answer. To the match-boys, our

existence is the darkest form of magic, usually

punishable by death.

They don’t even know what’s coming. How cute.

We shouldn’t be afraid of them.

No no no.

They should be afraid of us.”[92]

This poem of Lovelace’s is called ‘The first lesson in fire’. Here, Lovelace is talking directly to the men who attack and discredit women. She antagonises them by repeatedly calling them boys instead of men which makes amusement out of their masculinity. But more importantly, Lovelace writes that “the only thing we’re guilty of is being women”[93] and in reality, that is the only thing that the women who were accused to being witches were guilty of to.

How this is relevant today though is that a modern-day witch hunt isn’t the town declaring women to be supernatural beings, but now it’s women being called liars when they speak out about sexual assault. Lovelace noted to this comparison in her poem ‘We Lock Those Doors & Eat Those Keys’. Lovelace writes:

“Women are

Considered to be

Possessions

Before we are ever

Considered to be

Human beings,

& if our doors

& our windows

Are ever smashed in by wicked men,

Then we are deemed

Worthless-

Foreclosed.

Never sold.”[94]

It is interesting to see that Lovelace’s not only uses the word “Human beings”[95] here but that she capitalizes the word human. It can be assumed that Lovelace wanted to highlight that woman are not even considered to be the same race as our male counterparts. Moreover, Women during the 16th century witch-hunts and women now a still treated with the same objectification. The closest comparison between the two time periods can be seen thought the second wave feminist movement of that started in the 1960’s. Throughout the 1970s, “growing feminist and also public awareness about the issue of male violence against women find specifically directed at women by men prompted the need for explanation of this phenomenon.”[96]Protests proved that “domestic violence and rape were some of the earliest concerns, evidence from women made it obvious that these experiences were very widespread.”[97] The “rediscovery of the issue of male violence against women brought to the fore some very important questions about male female relations, including the role of male violence and, more recently, sexuality, in social control of women”[98] [Edwards 1987; Kelly 1988; Jeffries 1990). “Women's widespread experience of rape was being uncovered through consciousness raising and the sharing of those experiences, as well as three research built on woman's experience”[99] [brown miller 1987; 8 dash 9; Gryphon 1971; Russell 1973: 1975). It has appeared that the treatment of women have not changed since the mistreatment of the women who were accused of witchcraft in the 16th century. Women are objects, and when they are no longer seen as the perfect form they are deemed as worthless to society. Lovelace’s work inspires women to speak out against the same injustice that those innocent women who were accused of witchcraft was; therefore, this is just another example of why witches were in fact feminist icons.

The Power of the Menstrual Cycle and Stephen King’s ‘Carrie’

Whether or not you believe in witches or not. The Western societies “discomfort with menstrual blood is evident in its relative absence from just about every aspect of life;”[100] which can be seen from the constant absence of blood from any advertisement for feminine hygiene products. Possibly because “menstrual blood was still intimately tied to the historic view that it was somehow different from other kinds of blood.”[101] This is largely down to “its regular and predictable appearance, as well as its undeniable link to the place where babies are made”[102] and that it was only related to one specific gender. In her 2006 article, ‘Menstrual Fictions: Languages of Medicine and Menstruation, c. 1850–1930,’ Julie-Marie Strange wrote that “the idealisation of woman as procreator pervades the language of menstruation,” explaining that “the very creation of a menstrual knowledge which was inextricable from notions of gender located gynaecology in the realm of fiction rather than fact.”[103] However, in cultures like the Egyptians, Native American tribes (including the Nootka and the Navajo) as well as Eastern Asian, all “engaged in ceremonial events around menstruation, primarily the first period.”[104] So, why is there this disparity in attitude towards the female menstrual cycle between cultures? This section will look at the connection between the menstrual cycle and female power.

In September of 2019, whilst I was reading Vouge I came across and interesting article by Lisa Stardust titled ‘Menstrual Blood Magic: 3 spells for your period’. Stardust’s explains that even though the menstrual cycle is completely natural, the “modern society has stigmatized menstruation”[105] through tampon commercials promoting women to discreetly hide that they are experiencing a period. However, Stardust periods are actually an integral part of female magic. In witchcraft, “one’s menstrual cycle is considered to be an extremely powerful time. Particularly when it lines up with full moon (though it should be noted that, scientifically speaking, the moon does not influence when you get your period), our menstrual cycles can connect our bodies to the universe, which is the intent of magic.”[106] For the majority of the time, the high priestess of covens would often be a women who’s menstrual cycle matched up to the moon’s cycle as it was believed that she was more connected to the universal powers and therefore she held supremacy over her sisters. It has to be stated that “periods are a fact of life for tens of millions of humans around the globe, the reality of a period — that for several days, multiple times each year, a person bleeds somewhat consistently — is often obscured by the ethos around them.”[107] In ‘Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation’, editors Thomas Buckley and Alma Gottleib explain that while the vast majority of documentation around menstrual mythology is negative, a handful of “ritualistic” uses for menstrual blood are positive — including but not limited to “the manufacture of various kinds of love charms and potions.”[108] Love potions in particular are one of the more frequent uses for menstrual blood in folk mythology. There is a particular lnordic ove potion that was recently featured in Ari Aster’s film ‘Midsommar.’

In the film, we witness Maja (played by Isabelle Grill) act out the love story tapestry that audience sees when the group first arrive at the Swedish commune. Maja places a love spell on Christian (played by Jack Raynor) by giving him a drink containing her menstrual blood as well as making him a pie that contains her pubic hair. Furthermore, there was one snippet from 1894 ‘Cincinnati Lancet’ contains a particularly offensive and telling anecdote about a “dark-coloured damsel”[110] who wished to ensnare a man by mixing menstrual blood into his coffee. Therefore, menstrual blood and the menstrual cycle has been a symbol of great power or a release of power.

The most significant moment of witches and the menstrual cycle (or just blood in general) in pop culture comes from Stephen King’s ‘Carrie’ (first published in April 1974). When we think of Stephen King, it is likely that would imagine blood and gore with an element of supernatural element and Carrie definitely fits perfectly in that category. Carrie is a “chunky girl with pimples on her neck and back and buttocks.”[111] A series of unfortunate events and past trauma, “traumatizes Carrie psychologically and results in Carrie turning into the monster figure of the story.”[112] Much of the book uses newspaper clippings, magazine articles, letters, and excerpts to tell how Carrie destroyed the fictional town of Chamberlain, Maine while exacting revenge on her sadistic classmates and her own mother Margaret. However, there are two specific scenes in the book that catapult Carrie from a normal, bullied girl to the ‘monster’ that the town released as Carrie. The first the iconic moment when Chris Hargensen Billy drop the pigs blood all over Carrie after she was crowned Prom Queen; this moment broke Carrie and that is when she used her “telekinetic powers to take revenge on those who torment her.”[113] The second scene is the Carrie traumatic experience of getting her period for the first time in the girls’ bathroom after gym class; this scene is what started the chain of events as this was the point that Carrie’s powers were released; as Carrie is exhibiting the idea of “first blood, then power”[114] that is associated with menstrual power. Carrie was left confused when everyone noticed “blood running down her leg”[115] before they started to chant ‘Period’ like it was an “incantation.”[116] The ceremonial of Carrie’s first period is made even more obvious as it was described as that “Carrie stood dumbly in the centre of a forming circle,” like she was a “patient ox”[117] waiting to be sacrificed while the other girl chanted around her. Furthermore, the book further explains that “both medical and psychological writers on the subject or an agreement that Carrie white exceptionally late and dramatic commencement of the mentor cycle might well have provided the trigger for her latent talent.”[118] Therefore, this is demonstrating the theory mystical power that the menstrual period could possibly have.

However, none of this explains why Carrie was so popular when it was released and how it still very currant in today’s pop culture. Alex E, Alexander explains that “Carrie is nevertheless a fairy tale: rites of passage, supernatural powers, magic and rites of sacrifice.”[119] Yet, “King’s novel is a special kind of fairy tale: it is an adult fairy tale explicit in matters of sex, killing and revenge if the young appreciate it, it may be because their tastes have grown ahead of their chronological age.”[120] Ultimately, “Carrie is metamorphosized into a monster by the society that tried to repress her”[121] whilst capturing the sympathy of the reader. Carrie “does not wilfully conduct evil against others but rather is forced to lash back at those who try consistently to eradicate the one thing that has significant meaning in Carrie’s adolescence: her self-worth.”[122]Carrie demonstrates that women can be incredibly powerful as she is able to easily overwhelm her entire town. The most important message though that Carrie expresses that when you (forcibly) put down a person who are subjected to the potential of the consequences of your actions, no matter how violent the repercussions may be. Though bit it a more dramatic message then the other images of the witch, Carrie represents the high-pressured catalyst women are put through even in today’s society. Carries inspires women to stand up for themselves against their oppressors but hopefully with a less deadly effect.

Not Being Ashamed of Our Sexual Desires with Jeanette Winterson’s ‘The Daylight Gate’

As noted in chapter 1, it wasn’t just women of the older generation who (with the perceived notion) no longer served society as she could no longer produce children, or she no longer had a husband or children/s to take care of. Any women who was explorative of her sexuality and wasn’t afraid to express it with confidence was also considered to be wicked and signed the deal with the devil. It is safe to say that famous artist like Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion and Lady Gaga would all be accused and executed for witchcraft for the way they freely express their sexuality. One author that has demonstrated this side of the witch is Jeanette Winterson in her novel ‘The Daylight Gate’ (first published in 2012) where she retells the most famous British witch trail in England, the 1612 the Trail of the Lancashire witches. This particular novel interesting expresses the two most common themes in witchcraft trails: “ugly-therefore-guilty” and “beautiful-yet-suspicious”[123]. This section will investigate the contemporary viewpoint of witches and how they demonstrated feminism.

Differently to our other modern texts about witches, ‘The Daylight Gate’ is based on a real-life witch trail that happened in Lancashire in 1612. The “Pendle witches is one of the many dark tales of imprisonment and execution at Lancaster Castle.”[124] Twelve people were accused of witchcraft; one died in custody while the other eleven went to trial. All but one was found guilty and executed. “Six of the eleven “witches” on trial came from two rival families, the Demdike family and the Chattox family…Elizabeth Southerns (aka “Old Demdike”) and Anne Whittle (“Mother Chattox”)”[125]. The “Old Demdike had been known as a witch for fifty years; it was an accepted part of village life in the 16th century that there were village healers who practised magic and dealt in herbs and medicines.”[126] It wasn’t till King James I’s book ‘Daemonologie’ that insighted fear into the village folk. Winterson’s novel depicts “the turbulent and controversial witch hunts of early 17th century England, a monstrous, but fascinating facet of female identity is outlined: the witch figure is constructed as an emblem and product of a backward and tyrannical patriarchal system, where woman is only appreciated because of her reproductive capacities, willingness to abide by men’s rules and religious affiliation.”[127] The witch is the transgressive femininity. Usually, women have to follow the simple concept of “if a woman speaks out, she is a monster; if she remains silent, she is an angel condemned to isolation and hysteria”[128](Leitch,2022). However, the witch takes on masculine attributes such as power, agency and violence so they become estranged to the cultural norm. Winterson’s novel centres around four witches waiting trail as well as a noble woman, Alice Nutter, who uses her influence to defend them. Alice nutter is initially presented as a “mysterious, Gothic heroine who possesses an unnatural youth,”[129] but she is a feminist of her times as she stands up for the rights of poor women. It is when the story progresses do, we gradually see that this is a tale of “Faustian and lesbian sacrifice”[130] as Alice Nutter was previously in a romantic relationship with the old had Demdike (Elizabeth. Device).

Alice expresses that “lesbian continuum” that “stands so feeble against the patriarchy which brands poor women as monsters or prostitutes and leads them to assume that the supernatural can be their only weapon.”[131] Winterson writes in her novel:

“Such women are poor. They are ignorant. They have no power in your world, so they must get what power they can in theirs. I have sympathy for them.”[132]

Biologically, for the majority of the time, men are physically stronger than women. It would be very easy for a man to overpower a woman and legally (at that particular time specifically) there was no protection for a woman. So, women had to find and use any means to provide safety for themselves and often that would be their sexuality to, in a way, manipulate the sexual drive of a man to get what they want. This is easily achieved because the female is body is constantly overly sexualized. However, what happens when the female body is sexualized but not available to men? This is the lesbian concept that heterosexual men have a struggled with for years. Catherine Clement associates “the witch with a repressed Imaginary and by extension, with the figure of the hysteric in their similarity regarding confinement and death; the sorceress pertains to the domain of Nature, as she “executes her transit imaginarily, perched on the black goat that carries her off, impaled by the broom that flies her away; she goes in the direction of animality, plants, the inhuman”[133] (Clement). It can also be seen by Mary Daly that witch hunts were a means of purifying society of women who did not harmonize with men’s interests:

“[...] the witchcraze focused predominantly upon women who had rejected marriage (Spinsters) and women who had survived it (widows). The witch-hunters sought to purify their society (The Mystical Body) of these “indigestible” elements – women whose physical, intellectual, economic, moral, and spiritual independence and activity profoundly threatened the male monopoly in every sphere. “[134]

Therefore, the main character of ‘The Daylight Gate’ are “the indigestible elements”[135] of society. The “strong and independent Alice Nutter thwarts male supremacy through her self-attained wealth and influence, whereas the witches threaten the stable patriarchal construct of marriage.”[136] Also, any other single and/or ugly woman, who are “self-sufficient, deviant aspects of femininity, living as outcasts on the outskirts of Pendle Hill”[137], have been forced into this dark local folklore. These women chose to not fit into the social norms that were forced upon women by the patriarchy. Hence, why these women were feminist icons that women today should be inspired by when overcoming the patriarchy.

In conclusion, the witch was an identity that was constantly oppressed and abused by the patriarchy. She was just a woman who was well educated on the female form as well as the properties of herbs and plants. Or she was a woman who wasn’t afraid of her sexual desires but also relished in them. Possibly, she actually was a woman that possessed powers unknown to any man. Whatever she was, she was a threat the patriarchy because she didn’t fit into their desired idea of what a woman is and how she should act. The witch was never more of a threat then when she formed together with likeminded women. However, it seems that saying that now there is now no fear to say publicly that you are a witch and/or practicing witchcraft. Many of those who practice witchcraft are very open about it especially on social media. This new free existence for the modern-day witch was helped largely down to help of positive images of witches being presented in pop culture as well as other feminist movements and linked modern day feminist problems with the problems faced by women who were accused of witchcraft. However, the modern-day image of the witch isn’t without her problems. Firstly, famous pop culture references of witches, like King’s Carrie, are mainly written by men as well as early writing of witches were also down by men. Therefore, the image of the witch is still being infiltrated by the patriarchy in some way. Hence, why one has to be incredibly careful on where the source is coming from as well as that person’s intention. Furthermore, it cannot be missed that the majority of the images of the powerful witch in modern culture is mainly an image of a white woman. In fact, the Goddess movement and feminist witchcraft, in particular, have been routinely criticized as being a ‘white women’s movement’ and the black feminist witch is often overlooked. Yet, the transgression against the female witch can be recognised by all women around the world. Ultimately, the witch was never dependant on a man; that is why she is a feminist icon.

Bibliography

· Alexander, A.E., 1979. Stephen King's" Carrie"-A Universal Fairytale. Journal of Popular Culture, 13(2), p.282.

· Aster, A. 2019 Midsommar; Square Peg Production scene from minute 45:31to minute 46:00

· Castiglione, G,B. 1650-1651 Circe with Companions of Ulysses Changed into Animals

· Daly, M. 1978 Gyn/ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism. Boston: Beacon Press,

· Deepwell, K., 2020. Feminist interpretations of witches and the witch craze in contemporary art by women. The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies, 21(2), pp.146-171

· Durer, A. 1500 Witch Riding Backwards On A Goat (Die Hexe)

· Edwards, J.R., Baglioni Jr, A.J. and Cooper, C.L., 1990. Stress, Type-A, coping, and psychological and physical symptoms: A multi-sample test of alternative models. Human Relations, 43(10), pp.919-956.

· Ehrenreich, B. and English, D., 2010. Witches, midwives, & nurses: A history of women healers. The Feminist Press at CUNY.

· Federici, S., 2018. Witches, witch-hunting, and women. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

· Gage, M.J., 2019. Woman, Church & State: The Original Exposé of Male Collaboration Against the Female Sex. Good Press.

· Goya, F., Witches' Sabbath (Goya, 1798).

· Griffin, W., 1995. The embodied goddess: Feminist witchcraft and female divinity. Sociology of Religion, 56(1), pp.35-48.

· Grossman, Pam, 2019 ‘Yes, Witches Are Real. Because I Am One https://time.com/5597693/real-women-witches/

· Hays, T.E., 1990. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation.

· Henesy, M., 2020. “Leaving my girlhood behind”: woke witches and feminist liminality in Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. Feminist Media Studies, pp.1-15.

· Hester, M., 2003. Lewd women and wicked witches: A study of the dynamics of male domination. Routledge.

· Homer, H., 2015. The odyssey. Xist Publishing.

· Juárez-Almendros, E., 2017. Disabled bodies in Early Modern Spanish literature: Prostitutes, aging women and saints. Liverpool University Press.

· King, S., 2015. Carrie. Luitingh Sijthoff.

· Klassen, C., 2012. The Metaphor of Goddess: Religious fictionalism and nature religion within feminist Witchcraft. Feminist Theology, 21(1), pp.91-100.

· Kristen, J., 2017. Witches, Sluts, Feminists, Conjuring the sex positive.

· Lazăr, M.C., 2014. “The Indigestible Elements”: Witches and Female Identity in Jeanette Winterson’s The Daylight Gate’. Indian Review of World Literature in English, 10(2), pp.1-9.

· Leitch, Vincent. B. (Ed.).2001 The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton& Company,

· Lewis, Ioan M. and Russell, Jeffrey Burton. 2021 "Witchcraft". Encyclopedia Britannica, , https://www.britannica.com/topic/witchcraft.

· Lovelace, A. 2014 The witch doesn’t burn in this one; Andrews McMeel Publishing

· Kansas City, Missouri, United States

· Matteoni, F., 2010. Blood beliefs in early modern Europe(Doctoral dissertation).

· Miller, M., 2019. Circe. Grupo Editorial Patria.

· NIKAM, S.V., Head, P.G., BIRAJE, M.R.J. and Mahavidyala, S.S.C., A Face of Horror in Stephen King’s Carrie.

· Olsen, H,B. 2017 The Mystical, Magical Properties of Period Blood https://medium.com/s/bloody-hell/the-mystical-magical-properties-of-period-blood-9a5b3e4c34ff

· Osmond, M.W. and Thorne, B., 2009. Feminist theories. In Sourcebook of family theories and methods (pp. 591-625). Springer, Boston, MA.

· Parry, H., 1987. Circe and the Poets: Theocritus IX. 35—36. Illinois Classical Studies, 12(1), pp.7-21.

· Plummer, K., 2002. Telling sexual stories: Power, change and social worlds. Routledge.

· Ramstedt, M., 2004. Who is a Witch? Contesting Notions of Authenticity Among Contemporary Dutch Witches. Etnofoor, pp.178-198.

· Rosa, S. 1664 ‘A Witch’

· Ross, K https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/circe-offering-the-cup-to-ulysses/john-william-waterhouse/9651

· Segal, C., 1968, January. Circean Temptations: Homer, Vergil, Ovid. In Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (Vol. 99, pp. 419-442). Johns Hopkins University Press, American Philological Association.

· Sempruch, J., 2004. Feminist constructions of the ‘witch’as a fantasmatic other. Body & Society, 10(4), pp.113-133.

· Stardust, Lisa. 2020. Here’s what it means to be a real life witch in 2020 https://www.instyle.com/lifestyle/witch-meaning-myths

· Strange, J.M., 2000. Menstrual fictions: Languages of medicine and menstruation, c. 1850–1930. Women's History Review, 9(3), pp.607-628.

· Spruijt, A.H.M., 2020. Fourth Wave Feminism In Contemporary Poetics: The Crossing of Categorical Boundaries (Bachelor's thesis).

· ‘The American Gyna͡ecological & Obstetrical Journal: Formerly the New York Journal of Gyna͡ecology & Obstetrics. V.1-19, 1891-1901, Volume 3

· Waterson, J,W. 1891, Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus

· Yarnall, J., 1994. Transformations of Circe: the history of an enchantress. University of Illinois Press.

[1]Grossman, Pam, 2019 ‘Yes, Witches Are Real. Because I Am One https://time.com/5597693/real-women-witches/

[2] Matteoni, F., 2010. Blood beliefs in early modern Europe(Doctoral dissertation).P.72

[3] Ibid, Matteoni, F., P.72

[4] Ibid, Grossman, Pam

[5] Lewis, Ioan M. and Russell, Jeffrey Burton. 2021 "Witchcraft". Encyclopedia Britannica, , https://www.britannica.com/topic/witchcraft.

[6] Ibid, Grossman, Pam

[7] Ibid, Lewis, Ioan M. and Russell, Jeffrey Burton

[8] Ibid, Lewis, Ioan M. and Russell, Jeffrey Burton

[9] Sollee Kristen, J., 2017. Witches, Sluts, Feminists, Conjuring the sex positive. P.57

[10] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.57

[11] Ramstedt, M., 2004. Who is a Witch? Contesting Notions of Authenticity Among Contemporary Dutch Witches. Etnofoor, pp.178-198.P.180

[12] Ibid, Matteoni, F., P.72

[13] Ibid, Lewis, Ioan M. and Russell, Jeffrey Burton

[14] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/religion/overview/witchcraft/

[15] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/religion/overview/witchcraft/

[16] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/religion/overview/witchcraft/

[17] Gage, M.J., 2019. Woman, Church & State: The Original Exposé of Male Collaboration Against the Female Sex. Good Press.P.98

[18] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.98

[19] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.98

[20] Juárez-Almendros, E., 2017. Disabled bodies in Early Modern Spanish literature: Prostitutes, aging women and saints. Liverpool University Press. P.83

[21] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.83

[22] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.84

[23] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.85

[24] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.85

[25] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.85

[26] Ibid, Juárez-Almendros, E P.85

[27] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.94/95

[28] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.94/95

[29] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.100

[30] Hester, M., 2003. Lewd women and wicked witches: A study of the dynamics of male domination. Routledge. P.1

[31] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.100

[32] Ibid, Gage, M.J P.100

[33] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.30

[34] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.30

[35] Ehrenreich, B. and English, D., 2010. Witches, midwives, & nurses: A history of women healers. The Feminist Press at CUNY.P.25

[36] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, D P.31

[37] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.40/42

[38] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, D P.32/33

[39] Ibid, Hester, M. P.1

[40] Ibid, Hester, M. P.1

[41] Ibid, Hester, M. P.1

[42] Ibid, Hester, M. P.1

[43] Henesy, M., 2020. “Leaving my girlhood behind”: woke witches and feminist liminality in Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. Feminist Media Studies, pp.1-15.

[44] Deepwell, K., 2020. Feminist interpretations of witches and the witch craze in contemporary art by women. The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies, 21(2), pp.146-171

[45] Ibid, Deepwell, K.,

[46] Ibid, Deepwell, K.

[47] Ibid, Gage, M.J

[48]Ibid, Gage, M.J

[49] Ibid, Gage, M.J

[50] Federici, S., 2018. Witches, witch-hunting, and women. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

[51] Ibid, Federici, S.,

[52] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, P.39

[53] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, P.39

[54] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, P.42

[55] Ibid, Ehrenreich, B. and English, P.42

[56] Klassen, C., 2012. The Metaphor of Goddess: Religious fictionalism and nature religion within feminist Witchcraft. Feminist Theology, 21(1), pp.91-100.

[57] Griffin, W., 1995. The embodied goddess: Feminist witchcraft and female divinity. Sociology of Religion, 56(1), pp.35-48. P.35

[58] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.37

[59] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.37

[60] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.37

[61] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.39

[62] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.39

[63] Ibid, Griffin, W. P.37

[64] Ibid, Klassen, C., P.97

[65] Ibid, Hester, M. P.1

[66] Ibid, Deepwell, K.

[67] Segal, C., 1968, January. Circean Temptations: Homer, Vergil, Ovid. In Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (Vol. 99, pp. 419-442). Johns Hopkins University Press, American Philological Association.P.420

[68] Homer, H., 2015. The odyssey. Xist Publishing. P.128

[69] Ibid, Homer, H P.128

[70] Yarnall, J., 1994. Transformations of Circe: the history of an enchantress. University of Illinois Press. P.10

[71] Ibid, Homer, H P.130

[72] Ibid, Yarnall, J. P.11

[73] Ibid, Homer, H P.132

[74] Parry, H., 1987. Circe and the Poets: Theocritus IX. 35—36. Illinois Classical Studies, 12(1), pp.7-21.

[75] Miller, M., 2019. Circe. Grupo Editorial Patria. P.173

[76] Ibid, Deepwell, K. P.147

[77] Ibid, Deepwell, K. P.147

[78] Ibid, Deepwell, K. P.147

[79] Goya, F., ‘Witches' Sabbath’ (Goya, 1798).

[80] Rosa, S. 1664 ‘A Witch’

[81]Durer, A. 1500 Witch Riding Backwards On A Goat (Die Hexe)

[82]Ross, K https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/circe-offering-the-cup-to-ulysses/john-william-waterhouse/9651

[83] Waterson, J,W. 1891, Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus

[84] Castiglione, G,B. 1650-1651 Circe with Companions of Ulysses Changed into Animals

[85] Sempruch, J., 2004. Feminist constructions of the ‘witch’as a fantasmatic other. Body & Society, 10(4), pp.113-133. P.113

[86] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.14/15

[87] Ibid, Sollee Kristen, J P.14/15

[88] Stardust, Li. 2020. Here’s what it means to be a real life witch in 2020 https://www.instyle.com/lifestyle/witch-meaning-myths

[91] Spruijt, A.H.M., 2020. Fourth Wave Feminism In Contemporary Poetics: The Crossing of Categorical Boundaries (Bachelor's thesis).

[92] Lovelace, A. 2014 The witch doesn’t burn in this one; Andrews McMeel Publishing

Kansas City, Missouri, United States P.14

[93] Ibid, Lovelace, A. P.14

[94] Ibid, Lovelace, A. P.27

[95] Ibid, Lovelace, A. P.27

[96] Ibid, Hester, M. P.58

[97] Plummer, K., 2002. Telling sexual stories: Power, change and social worlds. Routledge.

[98] Edwards, J.R., Baglioni Jr, A.J. and Cooper, C.L., 1990. Stress, Type-A, coping, and psychological and physical symptoms: A multi-sample test of alternative models. Human Relations, 43(10), pp.919-956.

[99] Osmond, M.W. and Thorne, B., 2009. Feminist theories. In Sourcebook of family theories and methods (pp. 591-625). Springer, Boston, MA.

[100] Olsen, H,B. 2017 The Mystical, Magical Properties of Period Blood https://medium.com/s/bloody-hell/the-mystical-magical-properties-of-period-blood-9a5b3e4c34ff

[101]Ibid, Olsen, H,B.

[102] Ibid, Olsen, H,B.

[103] Strange, J.M., 2000. Menstrual fictions: Languages of medicine and menstruation, c. 1850–1930. Women's History Review, 9(3), pp.607-628.

[104] Ibid, Olsen, H,B.

[107] Ibid, Olsen, H,B.

[108] Hays, T.E., 1990. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation.

[109] Aster, A. 2019 Midsommar; Square Peg Production scene from minute 45:31to minute 46:00

[110] ‘The American Gyna͡ecological & Obstetrical Journal: Formerly the New York Journal of Gyna͡ecology & Obstetrics. V.1-19, 1891-1901, Volume 3

[111] King, S., 2015. Carrie. Luitingh Sijthoff.P.4

[112]NIKAM, S.V., Head, P.G., BIRAJE, M.R.J. and Mahavidyala, S.S.C., A Face of Horror in Stephen King’s Carrie. P.46

[113] Ibid, NIKAM, S.V., Head, P.G., BIRAJE, M.R.J. and Mahavidyala, S.S.C., P.47

[114] Ibid, King, S P.146

[115] Ibid, King, S P.4

[116] Ibid, King, S P.6

[117] Ibid, King, S P.6

[118] Ibid, King, S P.9

[119] Alexander, A.E., 1979. Stephen King's" Carrie"-A Universal Fairytale. Journal of Popular Culture, 13(2), p.282.

[120]Ibid, Alexander, A.E.,

[121] Ibid, NIKAM, S.V., Head, P.G., BIRAJE, M.R.J. and Mahavidyala, S.S.C., P.52

[122] Ibid, NIKAM, S.V., Head, P.G., BIRAJE, M.R.J. and Mahavidyala, S.S.C., P.52

[123] Lazăr, M.C., 2014. “The Indigestible Elements”: Witches and Female Identity in Jeanette Winterson’s The Daylight Gate’. Indian Review of World Literature in English, 10(2), pp.1-9.

[124] https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Pendle-Witches/

[125] https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Pendle-Witches/

[126] https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Pendle-Witches/

[127] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[128] Leitch, Vincent. B. (Ed.).2001 The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton& Company,

[129] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[130] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[131] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[132] Winterson p.55

[133] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[134] Daly, M. 1978 Gyn/ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism. Boston: Beacon Press,

[135] Ibid, Daly, M.

[136] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[137] Ibid, Lazăr, M.C.,

[79]

[80]

[81]

[82]

[83]